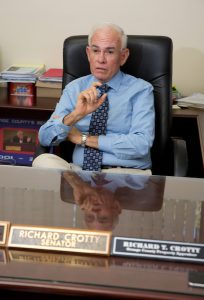

The first one in his family to step foot on a college campus, Rich Crotty has never been one to follow the beaten path. Reflecting on his rise from blue-collar background to storied political career, the former Orange County Mayor says that it wasn’t supposed to end as well as it did. Nearly 50 years after taking that first step into higher learning the one-time assembly line worker sits in an office decorated with plaques of distinction, memorabilia from government service and commemorative front pages.

In the decades following Crotty’s 1970 graduation from Valencia, he went from a dark horse candidate for state representative to supporting pivotal legislation in the Florida legislature to the board room of Orange County government, where, for a decade, he stewarded both economic development and environmental preservation as mayor in a county that was home to corporate powerhouses such as Disney and Lockheed Martin. The latter, in fact, played a special role in the beginning of Crotty’s career.

As a teenager he had hoped to work for the defense contractor when it was the Martin Marietta corporation. Eventually Crotty ended up on a busy assembly line, building missiles at the height of the Vietnam War. There, in spite of a paycheck many of his peers envied, he realized the job wasn’t all he had hoped it would be. He wanted an opportunity with more growth potential.

Some of his friends and colleagues were talking about a new, long-awaited higher education opportunity coming to town. Crotty was not sure if he was cut out for college, but before long he was driving his Plymouth Valiant down Oak Ridge Road and into the makeshift parking lot of Valencia Junior College, which was temporarily located at Mid-Florida Tech.

Crotty became an early classman at Valencia Junior College, where the potential energy among the student body was palpable.

“[Valencia] was new and exciting,” says Crotty. “People didn’t pay so much attention to the fact that classes were held in portables. There was more griping about the mud in the overflow parking lot. At certain times of the year the field just became a mudpit.”

Crotty flew through the coursework, while working the night shift at the Martin Marietta. He went on to transfer to the also fledgling Florida Technical University (known today as the University of Central Florida), an unwieldy transition that would have a lasting impression on him in his professional life. “The toughest day of my college career, by far, was trying to figure out what credits transferred,” says Crotty. “Some classes were worth partial credit and it was just a nightmare.”

After graduating from FTU, out in the real world, Crotty began his career in sales and management consulting, for three years working with a number of cities across the country under a grant from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Approaching his 30th birthday, he set his sights on public office, seeking a seat in the Florida House of Representatives. Despite his achievements in consulting — one of which was saving several cities millions of tax dollars by improving the efficiency of waste collection systems — on the campaign trail, he battled the perception that he was little more than an inexperienced graduate challenging a highly qualified and respected opponent.

“When I ran the first campaign it was not uncommon for the press to say, ‘Winter Park attorney Terry Hadley opposed by former FTU student,’” Crotty recalls. “The chances of me winning were pretty slim. When election night results were reported, of the ninety thousand people who voted I was ahead by 37 votes.”

Though education may have been the only significant notch in his belt at age 30, Crotty believes his college experience not only served him well on the campaign trail, but also set him up for success once in office. As one might expect of someone who spent 14 years in the state house, Crotty excelled in public speaking and debate throughout. But he credits Valencia with helping him overcome his fear of public speaking.

“The [Valencia] class I remember most was one that I was terrified to take – Introduction to Speech. But I had a really good professor. His name was Mr. Rogers,” Crotty recalls. “I learned more about myself in that class than anywhere else, and I realized I had the chops for it.”

Upon transferring to FTU he chose political science as his major, taking so many speech courses for electives that he eventually earned a second major.

With an oratorical rhythm found, Crotty was on a path to further improving the same education system that opened doors for him. Shortly after his election to office, he joined the Florida House of Representatives’ higher education committee and his first order of business supported FTU’s name change to the University of Central Florida.

His most memorable legislative moment, however, came when he had to debate in favor of a bill known as the Florida Prepaid College Program. It proposed to lock in tuition rates for parents who chose to save college funds, starting from their child’s infancy. The money could only be spent at Florida institutions of higher learning.

When the floor was open to final debate, a member who opposed the bill argued that it did not make financial sense.

“He was a financial planner, a wealth management guy, and he liked people to invest their money,” Crotty recalls. “So he said that if people invested their money elsewhere they’d have more money to send their kids to college. I said to the representative, ‘You’re absolutely right. If all you care about is money, this isn’t for you. But let me speak to the other members of the House. Imagine, if you will, young parents who never had a kid in college. If they choose to participate in this program, they’re going to raise that kid the entire time they’re in school, reminding them that their college is paid for and that they need to keep grades up and be a better student. If you don’t think [this program] is worth having parents engaged in their kids’ education then you’re right, it’s a bad investment. – To the other House members, I’ll tell you it’s the best investment you’ll make for families.’”

When the votes were tallied, the only vote against the program was that of the opposing representative. Today, over one million families have invested in the Florida Prepaid College Program.

Also during his tenure in the state legislature, Crotty supported legislation to resolve the problems he experienced as a transfer student a decade earlier. Common course numbering made a pivotal step for Florida in the effort to streamline the transition from state colleges to universities, ultimately paving the way for successful 2+2 models such as the Valencia-to-UCF Direct Connect program.

“The key to the whole process was a term known as ‘equal dignity,’ meaning a rising Valencia student, for example, should be treated the same as a UCF student that had been on the same campus all four years… There was a feeling that the transfer students would be viewed as less qualified when the facts show they are just as qualified.”

Crotty recognizes that, while the Direct Connect program has been extremely popular, there might be students facing similar challenges to those he faced 50 years earlier when he was a first generation college student working full time. His advice to students who think they might not be so qualified for college?

“Take advantage of it. It really is an opportunity… l didn’t feel financially or intellectually capable of going straight to a four-year university. Valencia was a confidence builder for me. And I’m just one of a million success stories coming from the college.”